- Is Cheating In A Game Unruly Behavior Against

- Is Cheating In A Game Unruly Behavior Among

- Is Cheating In A Game Unruly Behavior Definition

- Is Cheating In A Game Unruly Behavior Disorder

There’s a long history of athletes who have cheated. The examples are so rampant that it’s difficult to even summarize the presence of cheating in sports.

Three of the major American professional sports have been impacted. Major League Baseball saw the Black Sox Scandal in the early part of the 20th century, and in the later part of the century, doping literally altered record books. National Basketball Association referee Tim Donaghy was investigated by the FBI for betting on games that he officiated. Perhaps most recognizable to sports fans may be the National Football League’s controversy “Deflategate,” in which quarterback Tom Brady allegedly ordered deflated footballs used in the 2014-15 playoffs.

Cheating also extends to other sports, of course. In an infamous example, Soviet athlete Boris Onishchenko was banned for life from sports after he was caught electrically wiring his fencing weapon to go off at will in the 1976 Summer Olympics. Even more infamous was Lance Armstrong’s doping scandal, which stripped the cyclist of multiple achievements, including seven Tour de France titles.

Few people question whether cheating has impacted sports. But why have there been so many examples? What exactly causes athletes to cheat? This article takes a brief look at the psychology of cheating in sports.

Key Factors in the Psychology of Cheating in Sports

Who do people cheat in sports? Psychological research has provided insight into the sheer competitive nature of sports and the ethical complications of cheating. Those two factors offer perspective into why athletes are willing to cheat.

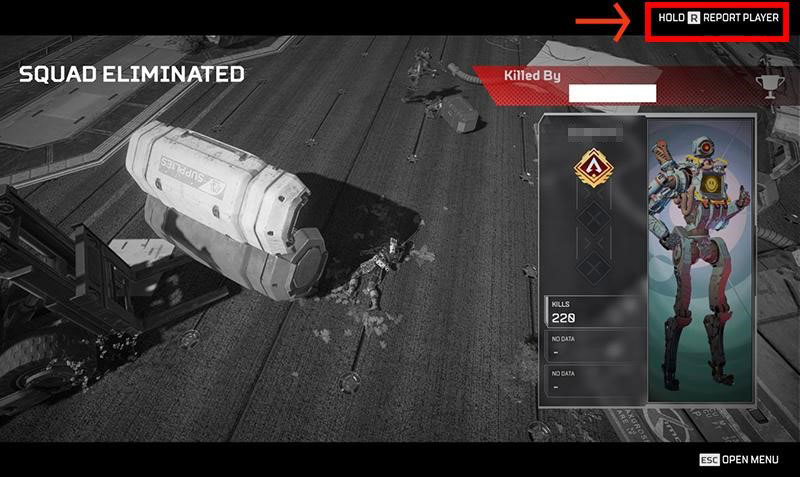

Soldier faces murder charge for ordering girlfriend’s son out of vehicle for ‘unruly’ behavior by busy highway Austin Birdsey, 5, was struck and killed by another driver on the highway. However, technically, as with live sports, it is cheating if the player is not playing the game in a formally approved manner, breaking unwritten rules. In some cases, this behavior is directly prohibited by the Terms of Service of the game. The fans were asked to leave with just seven minutes left in the game for “unruly behavior.” Others attending the game reported that the coach for Arlington High School apologized to Torrey. Managing Cheating When deciding how to respond to students who cheat, teachers need to think not just about punishing the behavior, but also about correcting it. Simply providing undesirable consequences for cheating, without focusing on the underlying reasons for the behavior, can have the effect of making students more crafty cheaters. Cheating, misconduct, deception and other forms of unethical behavior are widespread today, not just in business but in sports, government, schools, and many other arenas. While the media often focuses on extreme cases of cheating and sensational scams (such as Madoff’s ponzi scheme), less attention is paid to what researchers call. Because cheating is easier when we can justify our behavior, people often cheat in small amounts: We can come up with an excuse for stealing Post-It notes, but it is much more difficult to come up with an excuse for taking $10,000 from petty cash.

Emphasis on Winning

It might be an understatement to say that sports can be “competitive.” In fact, sports can be an important part of culture, according to Howard Giles in “The International Encyclopedia of Intercultural Communication.” For instance, in the words of a cultural historian Jacques Barzun, which are inscribed in the Baseball Hall of Fame, “Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball.”

Giles described how people “live in a globalized, sports-saturated world” that can put cultures and their values on display. Sports can also change the way that more specific groups interact and find their identity, including athletes, coaches, teams, and fans. Fans can be so involved that they have pregame anxiety and emotional experiences during games. They may even, without reason, blame losses on biased officiating (which can actually explain home field advantage) or cheating.

The stakes are high, and that’s especially the case at professional levels of sport. Winning is a necessary ingredient in the pursuit of excellence, and, as a result, athletes can take that further than others might. It’s reminiscent of the cliché that “winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.”

“Competitive sport often places individuals in conflicting situations that emphasize winning over sportsperson-ship and fair play,” according to the “Handbook of Sports Psychology.” “It would be wrong, however, to attribute this to the competitive nature of sport.” There are other factors at play. The next topic works hand-in-hand with the emphasis on winning to explain how athletes may turn to cheating.

The Ego and Moral Functioning

The concept of achievement goals is linked to potential cheating in sports. In task- and ego-oriented goals, there’s a fundamental difference in how athletes think of themselves and why they compete. Task-oriented athletes focus on hard work and self-development, while ego-oriented athletes are focused on being better than everyone else and believe skill to be a matter of innate ability.

According to the “Handbook of Sports Psychology,” studies have demonstrated relationships between task and ego orientations with sportsmanship and moral functioning. Compared to high task-oriented athletes, research points to how high ego-oriented athletes have lower sportsmanship, more self-reported cheating, and endorsement of cheating. Ego orientation can predict lower moral functioning.

Moral functioning can even take an unexpected turn with some sports cheaters. From research in Attitudes and Social Cognition, the notion that cheaters feel guilty after engaging in unethical behavior simply isn’t true. Over six experiments, unethical behaviors not only failed to trigger negative affect, but they triggered positive affect. Those types of behaviors can lead to a “cheater’s high.”

“These findings challenge existing models of ethical decision-making and offer cause for concern,” the study’s authors said. “Many ethical decisions are made privately and are difficult to monitor. Individuals who recognize, perhaps from experience, that they can derive both material and psychological rewards from engaging in unethical behavior may be powerfully motivated to behave unethically.”

Why Do People Cheat in Sports?

The psychology of cheating in sports is a complicated topic, and researchers are learning more about what drives people to violate the rules, use performance-enhancing drugs, or take part in some other method of cheating. However, the fundamental reason why people cheat in sports isn’t complex at all.

Athletes want to win. At the highest levels of sports, the difference between first and second place is often millions of dollars and a significant amount of fame. As a result, some athletes may believe winning really is the only thing. To them, the risk of getting caught and being labeled a cheater is worth the money and glory that being the best brings.

Ask Lance Armstrong. He lost everything, it may appear, after being stripped of his achievements and experiencing costly legal battles. Armstrong told USA Today that he had paid more than $100 million in legal costs, and that came before he settled a $100 million lawsuit with the federal government for just $5 million. However, even those numbers may be significantly lower than what cheating allowed him to win. According to Bloomberg in 2013, Armstrong’s riches totaled more than $218 million. At the peak of his career, he earned $28 million a year, Forbes estimated.

Was it worth it? In a BBC interview, Lance Armstrong said that if it was still 1995, he would “probably do it again.”

If you’re interested in the psychology of cheating in sports, you can learn more about sports psychology by earning your online MS in Exercise Science. You’ll receive a strong foundation in topics like exercise physiology and sports nutrition as well. Aurora University Online’s program offers two specializations in sports performance and clinical exercise. And through additional coursework and an internship or capstone experience, you’ll be prepared for either of the following industry-leading certification exams:

- The American College of Sports Medicine’s (ACSM) Clinical Exercise Physiologist (CEP) exam.

- The National Strength and Conditioning Association’s (NSCA) Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) exam.

All courses in the degree feature expert instructors with extensive experience in their fields.

Cheating, misconduct, deception and other forms of unethical behavior are widespread today, not just in business but in sports, government, schools, and many other arenas. While the media often focuses on extreme cases of cheating and sensational scams (such as Madoff’s ponzi scheme), less attention is paid to what researchers call “ordinary unethical behavior.”

For example: not reporting income on one’s taxes, buying clothing with the intention of wearing it once and returning it, stealing from one’s employer, or cheating on an exam. These forms of unethical behavior are often the results of ordinary people giving into the temptation to cheat when confronted with the opportunity to do so. When combined, these behaviors are extremely costly for both businesses and society.

On this page we describe some of the major areas of research addressing the nature and causes of ordinary, everyday dishonesty. (For simplicity, we use the terms unethical, immoral, and dishonest behavior interchangeably.)

IDEAS TO APPLY (Based on research covered below)

- Focus on the situations you place your employees into. Research suggests that people’s moral compasses are malleable and that various factors influence them. People do differ in their levels of personal integrity, but everyone is susceptible to environmental influences. Most people cheat under some circumstances. Ethical systems design is about changing those circumstances, rather than (or in addition to) trying to change the people.

- Walk the talk. It is critical for leaders to “walk the talk” (e.g. demonstrate ethical behavior rather than simply encouraging it) as their actions can have a profound influence on followers’ decisions to cross ethical boundaries. Peer influence is also very important since unethical behavior can be contagious. Creating honest cultures can reduce ethical failures by strengthening norms of appropriate conduct rather than strengthening rules.

- Consider both formal and informal structures and cultures. In organizations, both formal (e.g., reporting) structures and informal cultures (e.g., office norms) shape conduct. Both are important levers in reducing cheating behavior. Don’t make the mistake of focusing on only one.

- Balance outcomes with growth. Organizations need to measure outcomes. But don’t let outcome focus and goal orientation lead to “goals gone wild.” Cultivate a growth mindset in your organization, focusing on people’s efforts, improvements, and learning, rather than their talents, gifts, and outcomes. Growth mindsets lead to better performance and less cheating.

AREAS OF RESEARCH

- Does everyone cheat, or is it just the habitual cheaters? Lab studies repeatedly find that while not everyone cheats when presented with the opportunity, under some circumstances most people will do so to a certain extent. For instance, in a typical laboratory experiment examining cheating, people are asked to complete a task (e.g., do a math test under time pressure, roll a die) and then self-report their performance. The higher participants’ self-reported performance, the higher the payment they receive. The results usually show that people inflate their performance in order to earn more money, but only to a certain level above their real performance, and far below the maximum payoff possible. Additional research (Ariely, et. al, 2009) show that increased compensation often erodes performance.

- How do people justify their cheating? A common finding is that people don’t cheat as much as they can get away with; rather they cheat up to the point at which they can continue to believe that they are good people. Decades of research in social psychology have found that people strive to maintain a positive self-concept both internally and publicly. In addition, people typically value honesty, and have strong beliefs in their own morality. Thus, when facing the opportunity to cheat, people seem to experience a conflict between their desire to maintain a positive self-image by behaving honestly and their desire to advance their self-interest (e.g., get a financial benefit) by crossing ethical boundaries. One way to resolve this apparent conflict is to cheat only a little, reinterpreting the incriminated behavior as an honest mistake. In many situations people behave dishonestly just enough to profit from their unethicality (see Mazar et al. 2008, on how people use “inattention to moral standards” and “categorization malleability” to cheat while believing they are honest).

- Why do we let ourselves get away with cheating that we would condemn in others? We tend to be “moral hypocrites,” judging unethical behaviors in others but not in ourselves (Batson et al, 1999; Valdesolo and DeSteno, 2008). This disconnect between our judgments of others and ourselves is often not conscious, but rather is likely the result of very “ordinary” psychological processes. “Bounded ethicality” (Chugh, Banaji, and Bazerman, 2005) which compromises the unconscious and automatic processes that affect our ethical decision-making, enables us to see ourselves as ethical while engaging in behaviors we would judge as unethical for others. See our handout on Bounded Ethicality.

- What increases cheating? Research has found that several factors may increase people’s likelihood to cheat:

- Diminished self-control (i.e., the capacity to override impulses to assure actions are in line with goals and standards)

- Creativity (both one’s own creativity as well as creativity triggered by the situation or job one is in)

- Having room to justify one’s own behavior

- The use of stretch goals for performance

- Loss framing

- Insecure attachment

- A fixed mindset in which one’s abilities are not malleable

- What reduces cheating? Research has shown that interventions are most likely to reduce cheating if they increase the salience of a person’s sense of self. For example, people are less likely to cheat if they know they are being monitored. They’re also less likely to cheat in the presence of mirrors, evoking childhood memories, and even if they’re primed with nouns (“cheater”) rather than verbs (“cheating”). One study that demonstrates the importance of a salient sense of self was done (Shu et al. (2012)); they found that signing one’s name at the top of a form makes one more likely to fill out the form honestly than signing one’s name at the bottom. These studies show that when people are reminded of moral standards or of their sense of self, they are less likely to cheat.

- What factors have been shown to influence cheating in college students? A great deal of research has been done, much of it summarized in McCabe, Butterfield, & Trevino (2012): Cheating in college; Why students do it and what educators can do about it. Results show that students with low grade point averages cheat more, as do students who are involved in athletics, or fraternities and sororities. These findings suggest that the social context matters a great deal: Sports teams, fraternities, and sororities create environments in which cheating may be reinterpreted as helping a teammate, brother, or sister. Also important are students’ perceptions of peer attitudes and behaviors. If students perceive cheating as rampant among peers, they will cheat too. So, institutions that wish to address a cheating problem must create cultures of integrity. Honor codes are one approach that has been studied extensively and has been found to be effective if implemented seriously and consistently over time. As part of creating such a culture, it is important that students perceive the institution’s academic integrity policy to be understood and accepted among both students and faculty. And it is crucial that they perceive that those who cheat are disciplined.

- Do people look to norms more than to rules when it comes to ethics? When people face the decision to cheat, they often look to others to gain information about appropriate behavior. Lab experiments have shown that when people see others like them (e.g., their peers, or people they feel similar to) behaving unethically, they are more likely to cheat themselves. Interestingly, others’ exemplary ethical behavior affects their likelihood to behave honestly, but it has a weaker influence compared to others’ unethical behavior.

CASE STUDIES

Failures

Successes

- HBS case studies of culture turnaround after experiencing ethical failures:

OPEN QUESTIONS

- Among the situational and social forces that lead people to cheat, which ones are the most influential?

- Do interventions that work in one context (e.g., using honor codes in education) work in others to reduce cheating?

- What is the long-term effect of interventions that reduce dishonesty? What can be done to make them more self-sustaining instead of fading away in a year or two?

- How we can best equip people for the ethical challenges they face?

TO LEARN MORE

- David Hershleifer and Usman Ali‘s (2015) research on “Opportunism as a Management Trait: Predicting Insider Trading Profits and Misconduct”

- Dan Ariely‘s research on cheating, described in his 2012 book “The (Honest) Truth about Dishonesty.” New York: HarperCollins Publishers. (public library)

- Bazerman & Gino (2012). Behavioral ethics: Toward a deeper understanding of moral judgment and dishonesty. Annual Review of Law and Social Science.

- Moore & Gino (2013). Ethically adrift: How others pull our moral compass from true north. Research in Organizational Behavior

- Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45, 633–644.

Is Cheating In A Game Unruly Behavior Against

Relevant Videos

Is Cheating In A Game Unruly Behavior Among

- Francesca Gino discusses getting sidetracked by dishonest behavior:

- Here is an RSA animate of Dan Ariely’s book, The (Honest) Truth about Dishonesty:

- Robert Frank brings a Darwinian perspective to cheating and honesty in contemporary business:

- In a series of short videos, Linda Treviño discusses cheating in business schools:

- View more from our collaborators on this topic on our Cheating & Honesty playlist at the Ethical Systems YouTube channel.

This page is overseen by Francesca Gino, Dan Ariely, and Robert Frank, although other contributors may have added content.

Is Cheating In A Game Unruly Behavior Definition

Miscellaneous Links & References

(This is where other contributors might list relevant links/references they come across.)

Is Cheating In A Game Unruly Behavior Disorder

- Friesen, L. and Gangadharan, L. (2013). Designing self-reporting regimes to encourage truth-telling: An experimental study. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 94, 90-102. In an experiment involving a production task with self-reporting of accidents, the results showed that dishonesty was prevalent, but accident reporting was more frequent with compulsory reporting compared with voluntary regimes. The average proportion of accidents reported in the compulsory treatment was double that for the voluntary treatment (20% versus 10%).

- Helen Gilbert, “More than a third of purchasers prepared to lie when negotiating,” Supply Management, September 27, 2013. Lying was found to be an acceptable part of the negotiation process with 37 per cent or buyers prepared to tell an untruth, compared to 15 per cent of sales people. In addition, buyers admitted to being less honest in highlighting mistakes in their favor compared to counterparts in sales: 45 per cent versus 72 per cent.

- People actually get a boost of happiness after cheating, as reported in the New York Times (citing Ruedy, N., Moore, C., Gino, F., Schweitzer, M. (2013). The Cheater’s High: The Unexpected Affective Benefits of Unethical Behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(4), 531-548).

- Higher-status and more successful employees are more likely to engage in deception when faced with unfavorable social comparisons. Edelman, B.G. & Larkin, I. (2013). Social Comparisons and Deception Across Workplace Hierarchies: Field and Experimental Evidence. Harvard Business School NOM Unit Working Paper No. 09-096.

- Bounded ethicality is described in this chapter by Dolly Chugh, Mahzarin Banaji, and Max Bazerman.

- John Antonakis and colleagues on power, corruption and testosterone.

- Cohn et al. have an excellent study on “Business culture and dishonesty in the banking industry“